I have no affection for cigarettes. When I was growing up, both of my parents smoked, and wanting to be like them, I wanted to smoke, too. One day, sitting on my mother's lap, I asked her if I could have a puff of her cigarette. She handed it to me. I took a puff. I have never wanted to smoke anything ever again.

What I do have a fascination for, however, is cigarette cards. These cards were originally added to cigarette packages to stiffen them, and by the 1880s, manufacturers were printing advertisements on them, often including popular images that could be collected by consumers. Those images could be of sports stars, famous Native American leaders, national flags, exotic animals, or sometimes actors and actresses.

These cards can sometimes be found on Internet auction sites, and I've purchased a few in recent years, wanting to have images of performers from the

Regency era. The first one I bought was when I saw for sale a cigarette card of the actress

Eliza O'Neill identical to one in the collection of the New York Public Library. The card, issued by Chairman Cigarettes, probably dates to the 1920s. The reverse side gives information about O'Neill, including that she excelled in the roles of Belvidera, Juliet, and Mrs. Beverley.

Chairman Cigarettes appears to have been based in England at the beginning of the 20th century, but I've found scant information on them. Recently, I obtained a number of cigarette cards issued by Player's Cigarettes. John Player & Sons was based in Nottingham, but it merged with Imperial Tobacco Group in 1901. Under the ownership of Imperial, Player's issued a number of trading cards, though it had issued its own cards as far back as 1893. Probably around the same time Chairman issued the card showing O'Neill, Player's issued a series of 25 cards showing miniature portraits of great painters. (I've seen 1923 given as the year for this series, but cannot verify it.)

Many (though not all) of those miniature portraits displayed images of actresses. This one shows

Sarah Siddons, who according the the reverse side was "one of our greatest tragic actresses." Siddons first appeared on the London stage in 1775, but her first great success did not come until seven years later, when she appeared at Drury Lane as Isabella in an adaptation of Thomas Southerne's

The Fatal Marriage. The Player's card calls this performance "a triumph almost unequalled in the history of the English stage."

Siddons introduced her most famous role, Lady Macbeth, in 1785. This portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence, however, appears to show her in the role of Mrs. Haller from The Stranger, an adaptation Benjamin Thompson did of a melodrama by August von Kotzebue. Siddons was long the reigning tragic actress on the London stage. It was only after the retirement of Siddons that O'Neill came to London from Dublin, taking over many of the elder performer's roles, including Isabella and Mrs. Haller. Neither actress, however, had much of a gift for comedy. The great comedic actress of the period was Dora Jordan.

Here's a Player's trading card showing Jordan. As the card states, the image is based on a painting by George Romney. Jordan's real name was Dorothea Bland, but for obvious reasons, the actress changed it. Like O'Neill, she was born in Ireland and rose to fame in Dublin. Jordan made her London debut at Drury Lane in 1785, the same year Siddons first wowed audiences as Lady Macbeth. Rather than competing with the great tragedienne, Jordan gravitated toward comic roles, making her London debut in the role of Peggy, the protagonist of David Garrick's bowdlerized version of

The Country Wife.

Jordan was just as famous for her personal life off of the stage as she was for the roles she played on stage. In 1790, she became the mistress of the Duke of Clarence, a younger son of the reigning monarch, George III. They had ten children together, but sadly, the Duke could not marry her. After all, she was a humble Irish actress, and he was in line to ascend the throne. In fact, when his elder brother died in 1830, the Duke became King William IV. By that time, poor Jordan was dead. Her body was buried in a cemetery on the outskirts of Paris.

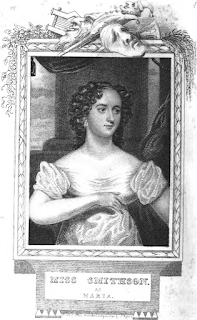

Another Regency actress, Maria Foote, appears on this Player's card, based off of a portrait by George Clint. Foote made her London debut at Covent Garden in 1814, as did O'Neill, but while O'Neill went on to massive fame as an actress, Foote did not. As the reverse side of her trading card puts it, she was "more celebrated for her beauty than for her acting." After her debut in

The Child of Nature by fellow actress

Elizabeth Inchbald, Foote went on to perform numerous Shakespearean roles, including Miranda in

The Tempest, Lady Percy in

Henry IV, and Helena in

A Midsummer Night's Dream.

Foote also played a key role in

Virginius, a new play by James Sheridan Knowles that after a brief run in Glasgow made its London premiere at Covent Garden in 1820. Foote played Virginia, the virtuous daughter of the title character. Virginia falls in love with Icilius, but the tyrant Appius lusts for her, and claims she is secretly the daughter of one of his slaves, sold to Virginius's now conveniently dead wife, since she was allegedly barren. The play made the new British king, George IV, rather nervous, since he was known for treating his wife and numerous mistresses not terribly well.

When I bought several Player's cards from a vendor, he kindly sent for free this 1930s card as a thank you. The card shows

Nell Gwyn, who according to the reverse side of the card rose from being "a fruit hawker in the precincts of Drury Lane Theatre" to eventually becoming "enrolled a member of the King's Company of Players." This was during the

Restoration under Charles II, and the king himself "fell a victim to her charms" as the card says. It was allegedly Gwyn who persuaded the king to complete the construction of Chelsea Hospital to provide a home for discharged soldiers.

The card is one of a series of 25 "Famous Beauties" taken from drawings by A.K. Macdonald. Other "beauties" drawn by Macdonald included Catherine the Great, the Queen of Sheba, and Pocahontas, so including the actress is quite a compliment. Gwyn was a close associate of the playwright Aphra Behn, who dedicated her play The Feigned Courtesans to the actress.

While I certainly am not a fan of the cigarettes that led to the creation of these cards, I'm glad many of the cards are still around today. They give us a fascinating glimpse not just of the world that created them, but also of the way that world looked back upon its own past.