The Victorian actor Samuel Phelps was described by his biographer Richard Lee as "the last typical classic actor of the English theatre." Lee knew Phelps, and shortly before the great actor died, he had agreed to perform in a comedy Lee had written called Cent per Cent. Alas, he never performed that play, but he appeared in so many other great shows!

Born in 1806, Phelps was the son of a wine merchant. His family valued education, and his younger brother Robert eventually led Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge, and at one point even served as Vice-Chancellor of the university there.

Arriving in London as a young man, Phelps took a job in a printing office, where his foreman was Douglas Jerrold, who had not yet risen to fame writing such plays as

Black-Eyed Susan and

The Rent-Day. Phelps invited Jerrold to watch him act in an amateur production of

The Castle Spectre by Matthew G. Lewis. According to Phelps, after the performance "Jerrold told me that by dent of hard study, luck, and patience I might in time act well enough to get thirty shillings a week."

Well, Phelps later made far more than that! His professional debut occurred in 1827 at the Queen's Theatre off of Tottenham Court Road, which later came to be know as the Prince of Wales's Royal Theatre. Phelps, then 21 years old, appeared as Captain Galliard in the farce XYZ. He then joined a company performing in the northern circuit, and according to Lee, Phelps "rapidly became a recognized stage favorite throughout the North of England, in Scotland, and, across St. George's Channel, at Belfast and Londonderry."

Ten years later, in 1837, Phelps made his debut at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in Thomas Otway's tragedy

Venice Preserved. Phelps played Jaffier opposite the Pierre of William Charles Macready, an actor who would be both his colleague and his rival for many years to come. Phelps accompanied Macready when the star actor took over the management of the rival Theatre Royal at

Drury Lane. It was there that Macready staged Robert Browning's tragedy

A Blot in the 'Scutcheon with Phelps as the lead, and then abruptly cancelled it.

"Though its success was undoubted," Lee writes, the play "for reasons never publicly stated, disappeared from the bills after the third representation." Macready was jealous of Phelps's success, but he also had bigger things to worry about as manager of Drury Lane. In 1843, the theatre's owners declined to give him a decrease in rent, and Macready responded by petitioning parliament to end the monopoly the two patent theatres had on performing spoken-word drama. The result was the

Theatres Act, which paved the way for the so-called minor theatres like Sadler's Wells to perform more serious fare than

melodrama and burletta.

Phelps, together with Thomas L. Greenwood and the actress

Mary Warner, took over the management of Sadler's Wells. At first, they planned to stage melodramas, as the house always had, and they even determined to get a fresh one written by Zachary Barnett to inaugurate their new management. When Barnett's melodrama was not forthcoming, however, and with the opening date of Sadler's Wells already advertised, the experienced, classical actors decided to begin with what they knew best. Instead of using a melodrama, they opened with

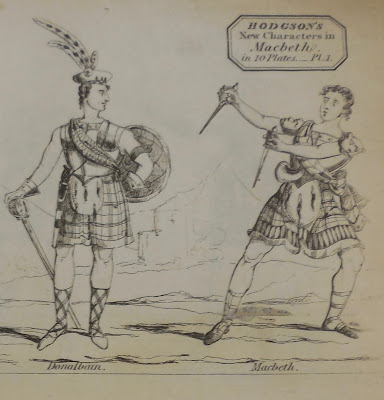

Macbeth. Phelps and Warner played the two leads, and according to Lee, who was there that night, the audience "was hushed by its attention to the action of the tragedy to such perfect stillness as quickened the sense to hear the faintest whisper from the stage."

The trio of managers quickly abandoned their plans to produce melodramas. The Theatres Act now allowed Sadler's Wells to produce any type of show it liked without having to split legal hairs over exactly how many songs were needed to qualify a piece as melodrama or burletta. For a while, they did try to produce new works, but after three new plays in a row failed, and a fourth was not likely to be ready for production, they went back to the classics.

Phelps was particularly known for his stagings of works by William Shakespeare. Of the plays accepted to be in the Shakespeare canon at the time, Phelps staged all of them at Sadler's Wells except the

Henry VI trilogy,

Troilus and Cressida, and

Richard II. Was he the last typical classic actor of the English theatre? I don't know, but he was probably one of the best.