Back in the 1950s, the critic M.H. Abrams published an important book on Romantic literary theory called The Mirror and the Lamp. The title comes from a major shift Abrams believed happened at the end of the eighteenth century. Since the days of Plato and Aristotle, the major metaphor for art had always been a mirror being held up to nature. With Romanticism, however, the metaphor shifted. Art became a lamp, radiating from within the artist into the outside world. Since we made that shift, Abrams argued, art has never been the same.

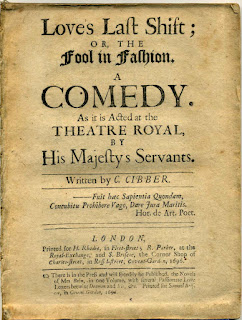

In his first chapter, Abrams lays out his now famous coordinates for art criticism. All art is related to the universe around it, to its audience, and to its artist. The relationship of art to the universe is explored by mimetic theory. This is the approach of Plato in The Republic and of Aristotle in The Poetics. In his Ars Poetica, however, Horace takes a pragmatic approach, using criticism to show how an artist can more effectively use poetry to move an audience. This is also the approach of Sir Philip Sidney, who in The Apologie for Poetry sees art chiefly as a means to an end. Abrams includes in this second pragmatic category Samuel Jonson, who was troubled by the fact that Shakespeare "seems to write without any moral purpose."

The breakthrough of Romanticism related art back to the artist, creating an expressive theory of criticism. Abrams cites William Wordsworth's 1800 preface to Lyrical Ballads, which defined poetry as "The spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings." During the Victorian era, John Stuart Mill and Thomas Carlyle continued to develop this theory, raising expressive theory to a form of hero worship of the artistic genius.

There is of course one other way of looking at art, and that is to look at the art itself, disconnected from the world, from the audience, even from its creator. Abrams calls this an objective approach, though he does not imply a moral judgment here. Objective criticism, as practiced by formalist critics including T.S. Eliot, is not necessarily more truthful. It simply is limiting its approach to the work of art and nothing else. It agrees with Archibald MacLeish that "A poem should not mean / But be."

A mimetic approach, of course, does not always mean that the world is portrayed precisely as it is. An eighteenth-century essay sometimes attributed to the playwright Oliver Goldsmith uses the analogy of sculpture to describe how artists pick and choose pieces of the world they wish to represent. According to the essay, a sculptor will take the best parts "from a great number of different subjects" to form "an ideal pattern."

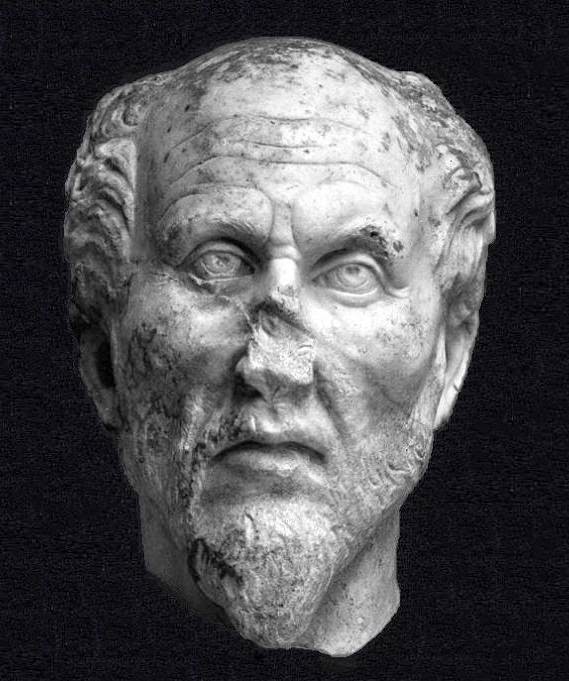

However, there was an even more radical idea lurking in the ancient writings of Plotinus. The Neoplatonist philosopher saw artists as representing not an object in the world, but an abstract ideal form that exists independently of the world. As Plotinus put it:

The arts are not to be slighted on the ground that they create by imitation of the natural world… we must recognize that they give no bare reproduction of the thing seen but go back to the Ideas from which Nature itself derives, and, furthermore, that much of their work is all their own; they are holders of beauty and add where nature is lacking. Thus Pheidias wroght the Zeus upon no model among things of sense but by apprehending what form Zeus must take if he chose to become manifest to sight.

This seed planted by Plotinus came to fruition during the Romantic era. Abrams quotes Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who said the goal of the Fine Arts was "to make nature thought, and thought nature." According to Coleridge, beautiful images "though faithfully copied from nature, and accurately represented in words, do not of themselves characterize the poet." It was instead the poet's job to use images to show, if not the world of ideal forms, the world of emotion within the mind of the poet. Instead of the mind being a tabula rasa of John Locke, simply being written upon by the world, the Romantic mind projected outward, inscribing itself upon the world around it.

The expressive theory of art travelled a long road from the Neoplatonists to Romanticism. Abrams gives special attention to the ancient philosopher Longinus, author of On the Sublime. Longinus held that "there is no tone so lofty as that of genuine passion, in its right place, when it bursts out in a wild gust of mad enthusiasm." He found sublime poetry to be the echo of a great soul. This way of thinking led Romantic theorists to elevate the ancient Hebrew poetry of the Bible to a level akin to that of the ancient Greeks, and to elevate lyric poetry above that of epic poetry, which had previously been seen as the ideal.

Wordsworth and Coleridge took similar but slightly different approaches to this new way of thinking about poetry. Wordsworth advocated "stripping our own hearts naked" and looking to those "who lead the simplest lives." Coleridge did not disagree, but he felt more was necessary to create great poetry than to simply capture the primitive language of rustics. Coleridge's so-called dynamic philosophy emphasized the mind's almost mystic ability to bring about harmony among contraries. According to Coleridge, the poet:

Diffuses a tone and spirit of unity, that blends, and (as it were) fuses, each into each, by that synthetic and magical power, to which we have exclusively appropriated the name of imagination. This power… reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant qualities.

The next generation of Romantics continued to develop these expressive theories. Percy Bysshe Shelley embraced a sort of Romantic Platonism, writing that poetry "is the very image of life expressed in its eternal truth." John Keats embraced the enthusiasm of Longinus, writing that "the excellence of every art is its intensity." John Keble gave a famous definition of poetry as "the indirect expression in words, most appropriately in metrical words, of some overpowering emotion, or ruling taste, or feeling."

Abrams himself favors a different definition, one coined by a mysterious writer who signed his name "S" in an article called "The Philosophy of Poetry" which appeared in Blackwood's Magazine in 1835. Abrams writes that in all probability this "S" was Alexander Smith, a Scottish scholar who had to retire from teaching early due to poor health. In any case, for "S" prose is the language of intelligence, while poetry is the language of emotion. Thus prose communicates our knowledge about objects while poetry expresses how these objects affect us. As the Blackwood's article puts it, poetry "is essentially the expression of emotion; but the expression of emotion takes place by measured language (it may be verse, or it may not)--harmonious tones--and figurative phraseology."

According to "S" a line like "My son Absalom" is not poetry, but the Bible is poetic when King David laments "oh! Absalom, my son, my son." Though the interjection of "oh" and the repetition of "my son" don't actually add any meaning to the phrase, they take the passage beyond a mere statement of fact to become an expression of a deep emotion. But how do poets, dramatic or otherwise, create works that express such emotions?

This brings Abrams to the shift from mechanical to organic theories of creation. Up through the eighteenth century, most theorists saw the process of creation as one of construction. A playwright, for instance, built a play in the same way a shipwright builds a ship. It was up to the writer to assemble together all of the elements of a play according to a preordained plan. In so doing, an artist had to build a play, or poem, or statue, according to certain fixed rules, just as a shipwright must construct a vehicle that will be inherently bound by the laws of physics. As the Scottish poet James Beattie put it in 1776:

It would be no less absurd, for a poet to violate the essential rules of his art, and justify himself by an appeal from the tribunal of Aristotle, than for a mechanic to construct an engine on principles inconsistent with the laws of motion, and excuse himself by disclaiming the authority of Sir Isaac Newton.

Coleridge replaces this mechanical model with a new one, that of an organism that grows naturally, assembling together a variety of elements without needing to be conscious of how it does so. In a letter to Wordsworth, Coleridge equated the philosophy of mechanism to that of death. Art, rather, was a living thing, much like a plant that grows from a seed, assimilating earth, air, light, and water into something new. Artists, though they might follow a natural pattern, need not be any more conscious of rules than an oak tree is aware of how it grows from an acorn.

This unconscious quality of genius became an important part of Romantic theory. Prior to Romanticism, critics recognized natural genius, but rarely praised it. In a typical passage in The Spectator, Joseph Addison compared natural genius to a wild landscape with no order or regularity. Artful genius, on the other hand, was "the same rich soil under the same happy climate, that has been laid out in walks and parterres, and cut into shape and beauty by the skill of the gardener." Similarly, Alexander Pope saw Shakespeare as an instrument of nature, while Homer was a genius who had tended a mighty tree until it had produced the finest of fruit.

This prejudice in favor of artful genius, as opposed to natural genius, was not confined to literary critics. One of the greatest champions of artful genius was the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. While he did not advocate a strict following of arbitrary rules, Reynolds praised artists who could discover the tendencies of the natural world and recreate them in painting. Reynolds held that:

It cannot be by chance, that excellencies are produced with any constancy or any certainty, for this is not the nature of chance.... [T]he rules by which... such as are called men of Genius, work, are either such as they discover by their own peculiar observations, or... [are] not easily to admit being expressed in words.

Yet not much later, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, and others were praising the natural, unconscious growth of poetry from the pure, virgin mind of the poet, not from some system of scientific discovery. Where did they get this idea? Did they come up with it from the undefiled wells of their souls? No. They stole it. From the Germans.

Which brings us to the most thought-provoking (and ridiculous) subject heading in Abrams' entire book: "German Theories of Vegetable Genius."

A subject heading like that deserves its own blog post. Come back tomorrow to see what Abrams meant by that doozie.