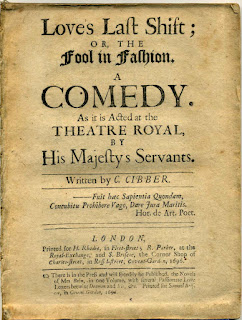

The actor Colley Cibber made his debut as a dramatist in 1696 with a play called Love's Last Shift, which while rooted in Restoration comedy of manners, looks forward to the sentimental comedies of the 18th century.

A shift is a lady's undergarment, so being down to one's last shift is an indication that this is the very last chance at something--in this case the last chance for Amanda Loveless to reclaim her rake husband who previously abandoned her for a life of dissipation abroad. (A shift, of course, can also be a trick or gambit, so the play's title has multiple levels of meaning.)

In the first act, Ned Loveless returns to London, where he hears the false rumor that his wife has died. Young William Worthy, learning that Loveless believes himself to be a widower, resolves to tell Amanda and scheme for a way she can reclaim him from his life of debauchery.

Their plan is to get Loveless to make love to his own wife, thinking she is only his mistress. At first, Amanda is reluctant. "To me the Rules of Virtue have been ever sacred;" she says, "and I am loth to break 'em by an unadvised Undertaking." After all, if she were to seduce her own husband, would she not become accessary to him violating his marriage vows?

Amanda overcomes these scruples and pursues her own husband in disguise, much to the delight of Worthy, who is pursuing his own plan to honorably marry a woman he loves. In earlier Restoration comedies, rakes were the heroes, but with the accession of William and Mary as co-monarchs during the Glorious Revolution, attitudes began to change. In the couplet that ends the third act, Worthy expresses his support for Amanda's reformation of Loveless and the rakish values he represents:

'Twere Pity now thy Hopes shou'd not succeed;

This new Attempt is Love's Last Shift indeed.

The fourth act shows Amanda seducing her husband and claiming that he has won her over to being a Libertine. The scene is reminiscent of the bed trick in Jacobean plays by William Shakespeare, including All's Well That Ends Well and Measure for Measure. However, its sexual frankness that deals so lightly with matters of adultery reflects a change that occurred after the Restoration. At the same time, the seduction is not adulterous, so the audience can revel in the faux immorality while actually cheering on morality.

This is why the play looks forward to the sentimental comedies of the eighteenth century. Characters are placed in difficult positions, but they get out of them through a reliance on virtue. Granted, virtue is forced to be deceptive, but this only presents new opportunities to discuss virtue's merits. When Amanda tries to undeceive her husband, she dramatically swoons, and only tells him the truth after she recovers. All ends happily, and virtue is at last rewarded.

That doesn't mean the play isn't funny, though, in spite of Oliver Goldsmith's later contrasts between sentimental comedy and the "laughing comedy" he preferred. The character of Sir Novelty Fashion (originally played by Cibber himself) provides plenty of comic relief through his foppish antics. That character reappeared in later plays as well, including John Vanbrugh's The Relapse, an unauthorized sequel that might well be more famous than the original.