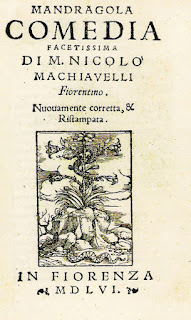

Though Machiavelli is most famous today for writing the cynical (or perhaps merely realistic) handbook The Prince, he also created quite a stir in the dramatic world by penning a cynical (or perhaps merely realistic) comedy Mandragola, or The Mandrake.

Machiavelli had already translated Terence's comedy The Girl from Andros when he wrote Mandragola, and he would later adapt Plautus's play Casina as the Italian comedy Clizia. However, his most famous play doesn't adapt a classical source, but instead comes up with something entirely new.

In the first act of Mandragola, we meet Callimaco, a young man in love with the married woman Lucrezia. She is too virtuous to return his affections, though, so he confides in his servant Siro a plan to win her. To make his plan work, he needs the services of the rascal Ligurio, who is quite... well... Machiavellian.

The second act shows Ligurio getting Lucrezia's husband to visit Callimaco, who poses as a doctor who can end the couple's childlessness. He tells the husband that there is no better way to ensure fertility than to have a woman drink a potion made from a mandrake root. The problem is that the next man to sleep with her is sure to speedily die.

Since the husband believes the story, the trouble is in convincing Lucrezia that the best way to honor her marriage is to sleep with a man other than her husband, thus ending the couple's childlessness and sparing her husband's life. In the third act, Ligurio and Callimaco enlist the help of both the corrupt Friar Timoteo and Lucrezia's own mother, Sostrata, who ultimately prevail with her.

The fourth act presents a complication when Callimaco realizes that he has offered to help the husband to kidnap an unsuspecting young man they can put in bed with Lucrezia. The problem is he himself wants to be that young man, so how can they get around this? Ligurio comes up with a plan to disguise the friar as Callimaco and have Callimaco make a funny face and put on ragged clothes so that he looks like a different person. The plan is so ridiculous, it actually works.

If you expect the dishonest characters in a Machiavelli play to get their comeuppance in the end, you will be sorely disappointed. All ends happily for the scoundrels, and they even exit going into church together. That last element might seem scandalous today, but the play's first documented performance in 1526 was during the carnival season, when licentiousness was winked at by authorities.

For that 1526 performance, Machiavelli composed four songs to go in between each act. The songs cover up the passage of time between the acts, and also comment upon the themes of the play. Mandragola is not for everyone, but it certainly had an influence on Renaissance drama.