I recently finished Sharon Marcus's delightful book The Drama of Celebrity. Focusing on the career of legendary actress Sarah Bernhardt, the book examines the interplay of celebrities, the media, and the various publics they both serve.

In her first chapter, "Defiance," Marcus discusses how the open defiance of convention practiced by celebrities like Bernhardt can actually enhance their fame. Celebrities create social exceptions in which they win the approval of society precisely by going against that society's demands. These celebrities shamelessly display their abnormalities rather than hiding them, as Bernhardt did with her unfashionably slender physique, large nose, and frizzy hair. "Defiant celebrities appeal not only to the marginal and to the outcast, but to anyone who has ever wanted to bypass conventions," Marcus writes.Her next chapter, "Sensation," looks at the desire of audiences and critics alike to willingly submit to a star's overpowering performance. As an example, Marcus cites Bernhardt's exit at the end of Act Four of Victorien Sardou's La Tosca. After killing the villain Scarpia, Bernhardt's character (according to Sardou's stage directions) "takes a carafe of water, wets a napkin, cleans the blood from her hands, and removes a small spot from her dress." Marcus notes, however, that the Chicago drama critic Sheppard Butler was fascinated by how Bernhardt "finger by finger, scrubbed the blood from her hand." By isolating each finger individually, Bernhardt slowed the action down just when the audience wants the heroine to get away as quickly as possible. At the same time, the stage business delayed the exit of the star everyone had come to see, prolonging the audience's enjoyment.

Chapter Three is entitled "Savagery" and deals with depictions of fans as being true fanatics who are capable of violent disorder. "Celebrities by definition attract large followings, but their very popularity usually inspires a vocal minority to resist the general euphoria," Marcus writes. Critics thus tend to characterize fans as "gullible, ignorant, and unruly." Depictions of Bernhardt's fans show them as anarchic, and after her first American tour, French caricaturists felt free to indulge in ridiculous stereotypes of Americans, frequently portraying Native Americans, African Americans, and Mormons in blatantly offensive ways to "other" her fan base in a drastic manner. At the same time, depictions of Bernhardt herself often exaggerated her large nose and unruly hair, sometimes adding Stars of David into pictures, just to make sure their anti-Semitism came across loud and clear.In "Intimacy" Marcus delves into attempts by fans and stars to form an important bond (or at least the illusion of a bond) between the two. While previous critics have discussed the "remediation" of a piece of art in one format into a new format, Marcus argues that fans clipping images and pasting them into a new context are not so much engaging in remediation as "resituation." Fans collecting photos, programs, articles, and ticket stubs in scrapbooks nevertheless engage with the material they resituate in a new location. In an era long before Pinterest or Tumblr, theatre fans could resituate images next to one another, and thus close "the gap between the players themselves and between celebrities and fan." According to Marcus, such resituation "registers work that hovers between production and consumption, looking and making, and speaks above all to a desire to bask in celebrities' presence by collecting, handling, and holding their representations."

Marcus's next chapter, "Multiplication," points out that while received wisdom tells us "multiplying the star's image dilutes celebrity and undermines the star's uniqueness" in reality "the more copies, the more celebrity." She interrogates the writings of Walter Benjamin, who postulated that the age of mechanical reproduction destroyed the aura of a unique object. Reproducibility, Marcus argues, replaced the aura with a "halo of the multiple" in which "apparent singularity is intensified by copying." Bernhardt, rather than diminishing hunger for her bodily presence with duplication, ensured that she would always have a live audience by posing for countless photographs, then by recording her voice, and later by starring in more than a hundred motion pictures. Though most of Bernhardt's films are now lost, they contributed to the demand to see her on stage, rather than decreasing it.Chapter Six on "Imitation" might seem closely related to the multiplication discussed earlier, but Marcus instead focuses on failures of imitation. Her central thesis of the chapter is that celebrity imitation is "a privilege that members of dominant groups often seek to deny those in subordinate ones." She bypasses José Esteban Muñoz's theory of disidentification to focus instead on depictions of ethnic and racial minorities failing in their attempts at mimicking white celebrities. While Marcus comes up with some compelling examples for her arguments, I found it strange that she seems to ignore so much theory from the past 20 years. For instance, in discussing a story about Henry James failing to impersonate Bernhardt, she notes that there is "more than a hint of gay shaming" in the account. Shouldn't that remind us of J. Halberstam's notion of "queer failure"? Like Muñoz, Halberstam is oddly absent from the book.

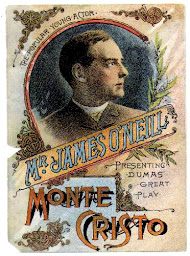

The following chapter on "Judgment" examines how not just critics but also ordinary fans engage in the process of evaluating performers. Throughout the nineteenth century, audiences became less rambunctious, more likely to sit quietly and listen rather than shout their approval or boo to show disdain. Fan letters and scrapbooks display the judgments of audience members, though, and Marcus provides plenty of amusing examples. A correspondent wrote to the actor Edwin Booth stating, "Your constant contortions render your part monotonous." Another theatre-goer, on seeing James O'Neill in The Count of Monte Cristo, wrote in a scrapbook that the performance had "sunk lower than any play which might have been acted and dramatized by a child of six years old."Marcus's final chapter on "Merit" looks not just at how fans have judged individual performers, but how they have compared those performers to one another. Originally, fans and critics alike relied on historical competition, for instance comparing Bernhardt to the earlier star Rachel Felix, or to Mademoiselle Mars, who originated the part of Doña Sol in Victor Hugo's Hernani. People could also compare stars to other living performers, especially when actors developed what Marcus calls shadow repertories. This is when actors deliberately pursue roles already made famous by their peers. Bernhardt did this when she played the lead in Sardou's La Sorcière, which had previously been played by Pat Campbell. In some cases, stars have even developed mirror repertories, in which two actors perform the same role in rapid succession.

Ultimately, the book argues that celebrity culture is a lot more complicated than many of its critics are willing to admit. Some celebrities like Bernhardt can deftly handle their fans and the press, but they are still reliant upon both. Media moguls play a big role, but they have failed again and again when they have tried to foist an unpopular celebrity on an unwilling public. Ordinary individuals have some agency, but our access to celebrities is always mediated through something else, whether it's a producer, a journalist, or an Internet platform. As Marcus concludes, "no single person or force can ever be assured of permanent victory."