I mean Lapine, who had collaborated with Stephen Sondheim on Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, and Passion had a new musical? Sign me up!

With music by Tom Kitt, who wrote Next to Normal? Of course I'm coming. You don't have to tell me what it's about! Wait, it's about Aldous Huxley, Clare Boothe Luce, and Carey Grant on an acid trip? Seriously? As they say, take my money, already!

Huxley has been a fascination of mine ever since I read Brave New World when I was in high school. I even wrote a play called The Four Doctors Huxley that was produced by a theatre in Jersey City. As for Luce, it's hard not to admire the technical brilliance of her play The Women, even if her right-wing politics tended to be revolting. And Grant? Who doesn't love Carey Grant, perhaps the greatest leading man Hollywood ever produced?

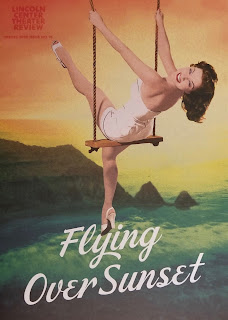

Well, the collapse of civilization as we knew it prevented the show from opening in 2020, but it's back now at Lincoln Center, and I finally got a chance to see it last night. The audience was sparse, due to the twin disasters of an omicron spike and bad reviews, but I enjoyed myself thoroughly. Choreographer Michelle Dorrance provides percussive movements that supplement Kitt's score, and the set by Beowulf Boritt works magic on stage.

What we're really here to see, though, is this trio of celebrities--so very different, yet so alike in many ways--interact with each other while tripping on a psychedelic drug. The problem is, people on psychedelic drugs don't necessarily interact. The journeys they go on are journeys within, which doesn't always lend itself to interpersonal connections. This means that Flying Over Sunset is about three individuals, not about finding community, which might make it an appropriate show for an individualistic society where community is considered suspect unless modified by the word online.

The first act in fact presents our three protagonists separately. First we meet Huxley, played by Harry Hadden-Paton, experiencing LSD for the first time while on a mundane trip to an L.A. drug store. He spots an art book being displayed alongside a plethora of other objects on sale, and his gaze at Botticelli's Judith with the Head of Holofernes becomes the operatic musical number "Bella Donna Di Agonia." Instead of dropping us immediately into a surreal hallucination, the show slowly builds to stranger and stranger visions, then gradually brings us back, much like the effects of a drug that build, peak, and fade.

Grant is the next to trip, taking the drug in a psychiatrist's office at the behest of his wife, Betsy Drake. This provides Dorrance with the opportunity to choreograph her most compelling tap number of the show, "Funny Money," in which Grant, played by Tony Yazbeck, dances with his younger self, played by Atticus Ware. Yazbeck has a particular challenge, playing the iconic Grant, since we all know the face of the man he is playing, but his dancing chops encourage us to suspend our disbelief and indulge in the fantasy. In real life, Grant famously described an acid trip he once had in which he imagined he was a giant penis launching into space. Naturally, the musical later stages this moment in the song "Rocket Ship."

The real star of the show, though, is Carmen Cusack, who plays Luce. We see Luce, by then a former congresswoman as well as the former ambassador to Italy, as she faces hearings in the U.S. Senate to be confirmed as ambassador to Brazil. No longer exuding the confidence she once had, though, Luce turns down the ambassadorship. At her estate in Connecticut, she takes LSD under the guidance of the writer and guru Gerald Heard (played by Robert Sella) and stops the show with her rendition of the title song "Flying Over Sunset."

At the end of the first act, the three protagonists meet up at the legendary Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles and decide to have an experience together at Luce's Malibu beach house. It is there, in a psychedelic garden, that Luce encounters her dead mother and daughter, both in "heaven" but different heavens, since her virginal daughter and not-so-virginal mother could never occupy the same astral plane in Luce's mind.

Flying Over Sunset, for all its pyrotechnics, is ultimately a quiet, simple show, about simple moments rather than grand gestures. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the moments of true connection between the characters happen only after the effects of LSD have abated. In our own world, fragmented and isolated by politics, disease, and other traumas, those moments of connection are more important than ever.