So yesterday I explained how M.H. Abrams in his book The Mirror and the Lamp traces English Romantic thought back to German theories of vegetable genius. Today, I want to take a look at how these theories influenced the way we think about art in the English-speaking world, particularly how we think about the theatre.

The Romantic critic William Hazlitt manifests the influence of German philosophy in his appropriately titled essay "Is Genius Conscious of Its Powers?" As is evident from the below quote, Hazlitt's answer to that question was an overwhelming "nein":

The definition of genius is that it acts unconsciously; and those who have produced immortal works have done so without knowing how or why.... Correggio, Michael Angelo, Rimbrandt, did what they did without premeditation or effort--their works came from their minds as a natural birth--if you had asked them why they adopted this or that style, they would have answered, because they could not help it.

Poet and playwright Samuel Taylor Coleridge had also read the German theorists. He drew upon them to argue that Shakespeare was great not in spite of his peculiarities, but precisely because of them. Coleridge praised the diversity of Shakespeare's writing, the mixing of comedy and tragedy, the trivial and the sublime. Coleridge appealed not to the ancient laws of Aristotle but "to the great law of nature that opposites tend to attract and temper each other."

Shakespeare was the great hero of the Romantics, but as much as they wanted to worship his genius, they were thwarted in their attempts to understand him as a man. This was not only because of the scanty information available about his biography. (The Romantics knew even less about Shakespeare than we know today, after diligent research in the early twentieth century by the likes of Charles and Hulda Wallace.) The problem was also that the plays of Shakespeare, precisely because of their universality, resist attempts to read them biographically.

Abrams calls this the "Paradox of Shakespeare," the fact that we know him so well and so little at the same time. The plays seem filled with their author, but at the same time he is nowhere to be found in them. That doesn't mean the nineteenth century didn't go looking, and few critics looked harder than Thomas Carlyle. Still, Carlyle had to admit defeat, writing in 1841:

But I will say, of Shakespeare's works generally, that we have no full impress of him there; even as full as we have of many men. His works are so many windows, through which we see a glimpse of the world that was in him.... Such bursts, however, make us feel that the surrounding matter is not radiant; that it is, in part, temporary, conventional. Alas, Shakespeare had to write for the Globe Playhouse: his great soul had to crush itself, as it could, into that and no other mould.

This image of the tragic Shakespeare, "crushed" in order to fill the theatrical world with his genius, seems to me an idea only the Romantics could have imagined. Other authors received similar treatment by Romantic critics, including Milton and even Homer, but Shakespeare remained the center of their literary universe, as he has remained to this day.

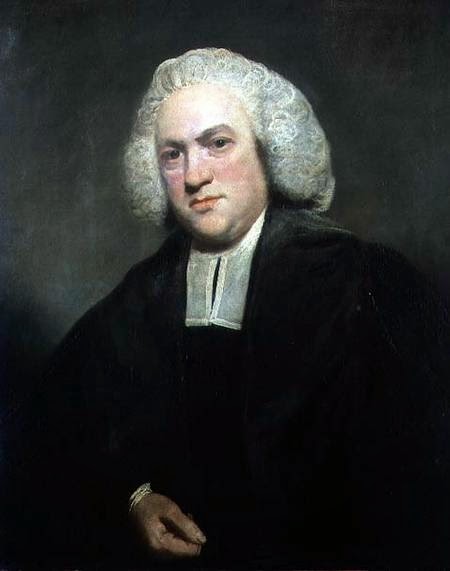

Abrams conjures up a number of Romantic critics to forward his argument. Some of those critics, like Carlyle, are well known today, but others remain obscure. My favorite discovery in reading the book was Joseph Warton, a poet and friend of Samuel Johnson who in the latter half of the eighteenth century wrote fervently about Shakespeare's ability in The Tempest to give "the reins to his boundless imagination" and portray "the romantic, the wonderful, and the wild, to the most pleasing extravagance."

Though Warton's work largely predates the Romantic literary revolution of the 1790s, he is clearly sympathetic to their cause. He wrote all the way back in 1753:

It is the peculiar privilege of poetry... to give Life and motion to immaterial beings; and form, and colour, and action, even to abstract ideas; to embody the Virtues, and Vices, and the Passions.... Prosopopoeia, therefore, or personification, conducted with dignity and propriety, may be justly esteemed one of the greatest efforts of the creative power of a warm and lively imagination.

Abrams links this passage directly to William Wordsworth, who in The Excursion instead of calling upon the hills and streams of the landscape for inspiration, looks instead "to the strong creative power / Of human passion." Here then is the light of the lamp, shining out of the poet, rather than a mirror passively reflecting the world around it.

Light, ever since Sir Isaac Newton broke it up into the colors of the spectrum, had never quite been the same, and Abrams dedicates the last chapter of his book to the dichotomy of science and poetry in Romantic criticism. Newton's prism seemed more like a prison to many Romantics. After seeing the great Edmund Kean acting Shakespeare, John Keats lamented the fact that "romance lives but in books" and "the rainbow is robbed of its mystery."

Keats later wrote in his long poem Lamia:

Do not all charms fly

At the mere touch of cold philosophy?

There was an awful rainbow once in heaven:

We know her woof, her texture; she is given

In the dull catalogue of common things.

Philosophy will clip an Angel's wings,

Conquer all mysteries by rule and line,

Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine--

Unweave a rainbow, as it erewhile made

The tender-person'd Lamia melt into a shade.

But not all Romantics maintained a hostility toward science. Keats' mentor Leigh Hunt once remarked that a man who thinks he is no poet after finding out the scientific cause of a rainbow truly "was none before."

John Stuart Mill, who was raised to be a utilitarian rationalist, but was then converted by the poetry of Wordsworth, eventually declared a truce. Passionately feeling the beauty of a cloud, he said, is no hindrance to understanding that it is actually a vapor of water suspended in air. Mill, though writing of poetry, could just as well have been speaking of the theatre when claimed:

Those who think themselves called upon, in the name of truth, to make war against illusions, do not perceive the distinction between an illusion and a delusion. A delusion is an erroneous opinion--it is believing a thing which is not. An illusion, on the contrary, is an affair solely of feeling, and may exist completely severed from delusion. It consists in extracting from a conception known not to be true, but which is better than truth, the same benefit to the feelings which would be derived from it if it were a reality.

Here we see a moral benefit of art, and in particular of the theatre, which invites the audience to enter fully into the lives of the characters on stage. Through drama, we come to identify with those outside of ourselves and recognize our common lot with all humanity. As Percy Bysshe Shelley put it:

A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains and pleasures of his species must become his own. The great instrument of moral good is the imagination; and poetry administers to the effect by acting upon the cause.

So there you have it. Art is not a mere ornamentation, but the greatest possible tool for the betterment of humanity. That's some pretty heady stuff, and in these post-Romantic times, maybe there are more than a few who believe that all the poetry of Alexander Pushkin is not worth a good pair of boots. Shelley, obviously, would disagree, and so would I.

Thus ends my explication of M.H. Abrams' classic book The Mirror and the Lamp. Now go out there and shine!

.jpg)